I recently finished Habibi by Craig Thompson. It’s an amazing piece of literature to say the least. The degree of experimentation, intricacy, and precision with which Thompson approaches his art is on display with each page. It blew me away! Reading Habibi has led me to start thinking about the nature of what makes a “great comic,” so that I can pass that knowledge along to my students.

The qualities of great comics are important to discern, especially when learning how to make comics. The following five qualities are the standards around which we at Making Comics (dotCom) are constructing our MOOC (massively open online course). Follow these principles when creating your own MOOC project.

5 Qualities of Great Comics:

1) Consistent Narrative

Narrative is the backbone of great literature. Simply put, narrative is the story that is being told. For the narrative to be clear in a comic, the reader must be able to understand what is going on in the story at all times. Consistent narrative helps the reader to feel comfortable with how the story unfolds. You can establish this in your own comic by including characters who are instantly recognizable, repetitive speech patterns, or even repetitive panel layouts.

Two-page spread from Watchmen #5 (titled “Fearful Symmetry”). The whole of this issue’s layout was intended to be symmetrical, culminating in this center spread. Note how the pages reflect one another. Art by Dave Gibbons.

2) Command Of Pacing

Pacing is the rate at which your reader takes in the story. It is determined by factors such as visual layout, density and nature of lettering, and emotional resonance. More than merely setting a rhythm and sticking to it, pace requires variety to make the story interesting. In Watchmen (by Alan Moore & Dave Gibbons), Moore slows the pace by deliberately dropping prose into the middle of chapters. It provides a break from the action, and allows a unique opportunity for character and world-building. The prose resonates and reinforces the themes of a chapter (i.e. Dr. Manhattan’s chapter features an excerpt from a science journal). Would I recommend that you end all the chapters of your comic in prose? Maybe! It all depends on if you feel that slowing down the pace of your comic would be consistent with the tone you are tying to establish.

3) Evolving Style

As an author working with an artist for the first time, understand the you cannot tell a story in the same way as you would with a different artist. It will almost never be possible. Or as an artist, periodically ask of yourself and those around you “does the style of my drawings match the story?” When I drew the following scenes from Hipster Picnic, in which Hawk and Steve transform from their cartoonish forms into their natural, zombie-like forms, I had to test and understand why I chose to depict the characters a certain way. Unfortunately, over the life of that initial series, the page format and approach to telling the story shifted frequently. Any potential readers would be confused because there was no consistent form or tone.

This is an example of what “not” to do over the span of a comic. I created Hipster Picnic from 2010-12 and it was always meant to be experimental. Unintentional style and format shifts obscured the narrative and ultimately prevented this initial run from gaining traction.

4) Elicits Passion

This one is a little esoteric but is easy enough to understand: does the writing of a comic lead you to believe that the author was invested in what they were making? I’ve read some terrible-looking comics where it showed that the artist clearly cared I’ve also read beautiful comics that seemed lifeless and lacked excitement. As a general bit of advice, try to only write about the things that interest you. If you can’t expect enthusiasm from the creator, why expect it from the reader?

5. Good Presentation

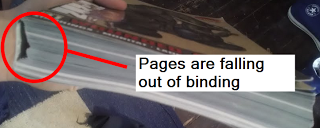

Richard Starking is one of the greatest letterers in the comic industry, and has been for some time. I first discovered his work through the first four collected volumes of his Elephantmen series. Each volume was massive! I loved the handling of multiple artistic approaches centered around a cohesive narrative. That’s why I was so disappointed to discover that my copy of Elephantmen was falling apart by the time I had finished reading it. Clearly, whoever printed the books must have done so on the cheap because the comics — which had 180 pages of art — cost only $15. Small wonder then that the binding glue was terrible! That experience made me reluctant to buy more Elephentmen comics, at least in print. The lesson? Consider presentation before you begin producing art for your project. I recommend finding a book that you like as a reference Research how that book was physically put together. Presentation can also extend to web design, as webcomics may not have a physical component to them. The goal is to plan ahead so that something as easily overlooked as presentation doesn’t distract from the quality of your work.

The End?

Now comes the hard part — study your own work to determine if it’s missing any of these qualities. If it is, don’t worry! Your comic may still be great. The strength of your story might compensate even if you’re lacking in any single category, presentation for example. Periodically run a mental checklist as you develop your comic to make sure that it achieves these standards. It will mean a better product in the end.

makingcomics.com

I have to say this has such good, well written, succient, and important points. Thank you for this, well written with good information.

wow this is awesome …I will like to work with comic companies like this because I have about three nice comics but don’t know how to get connected so to be known to the outside world.

Nice