One of the central truisms of being an artist is this:

You will have to do many drafts of your work.

It’s unavoidable. There is this myth among artists about how the masters of the craft were gifted from the beginning — that they went into their studios and produced works of greatness in a matter of hours. This is exacerbated by videos like this one, where it’s possible to watch a master like John Romita Sr. as he quickly busts out perfect drawings of Spider-man with a felt tip marker. Amazing, right? And deservedly so! John Romita Sr. has created comics since 1949 and has been drawing Spider-man since 1966. He’s had a lifetime of practice in order to reach a place where he can draw something amazing with minimal revisions.

About fifteen years ago, when I was really starting to commit to a life in the arts and illustration, you could have opened my sketchbooks and seen lots of drawings with a big “X” through them. Why did I do this? They weren’t perfect! I demanded perfection. When reading my Spawn and Spider-man comics I knew that my art needed to be like in those comics and anything short of that was not cutting it. I had a ruthless inner critic (still do to some extent) but in order to move forward I had to learn to listen to it less.

In 2008, I started working at a high school called High Tech High Chula Vista. It was the first time in my life I had been in a project-based learning environment. Sure, I had done projects in my Graphic Design & Art Education majors, but I had never been in a situations where all the students in school had to take art and were charged with creating amazing things. At first I was not good at working in a project-based learning environment because I made a critical error in my understanding of how I progressed in my own art. I thought the reason I improved my drawing capabilities had to do with the fact I had that harsh inner critic. For the first year that critic came out in me as a teacher. Quickly, students started to resent me and their projects which I oversaw wouldn’t be completed in time.

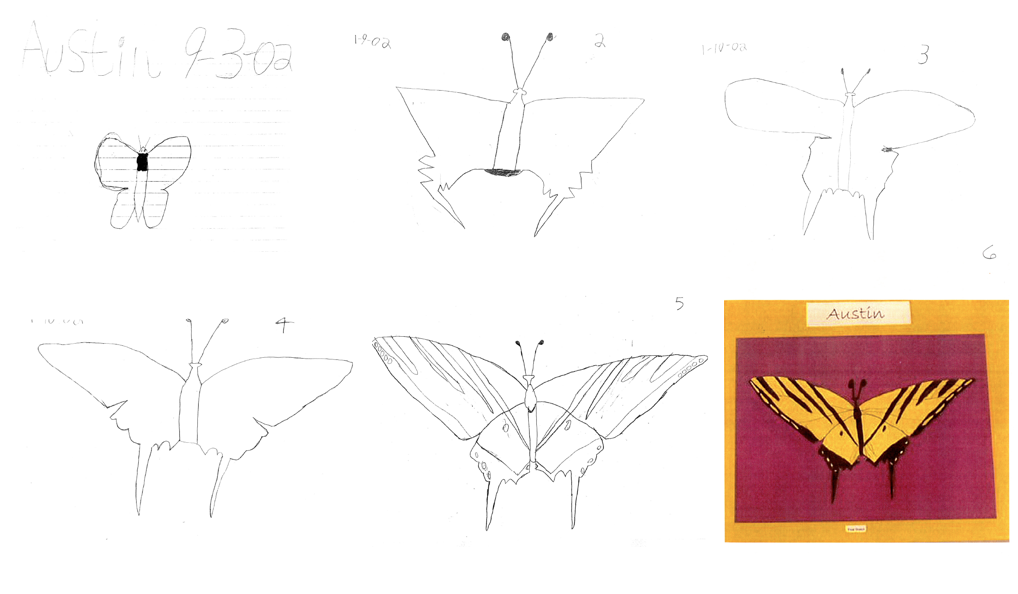

Then I met Ron Berger and saw this presentation about the role of drafting work and the role of critique in relationship to the drafting process:

Austin’s Butterfly Drafts from Ron Berger’s An Ethic of Excellence: Building a Culture of Craftsmanship with Students

My eyes widened and I realized the critical mistake I had made. I did not get better at illustration because of my harsh inner critic. In fact, that harsh inner critic had more to do with taste. The reason I got better at my own illustrations had more to do with the fact that I kept trying. Every time I started a new illustration I was practicing. I never considered that if I had had more feedback from others on each of my drafts of my work, I could have accomplished my goals even faster than I had previously thought.

I never thought that all of those drawings with X’s in them were just initial drafts of work leading to the work I am doing now. It is hard to remember even now that all of my art is just current drafts leading to the work I will be doing in the future. This means that you artwork is a record of your journey as an artist, and you are best served by understanding that the work you do at a given time is part of that journey (a.k.a learning opportunities).

I know, I know. You don’t want your artwork to be just a learning opportunity. You want it to wow audiences and bring them into the world that you have created. Guess what though? You have little control over how an audience experiences your work. By the time you present your work to them you can only see their reactions, so these reactions must serve as a learning opportunity.

We artists are people who tend to get invested in our work — in fact we are likely to spend way more time creating work than presenting it to audiences. In my experience, the best way to enjoy making art is to find a way to relax and view each “failed” effort as part of an ongoing process. I have to constantly remind myself “Patrick, if you want to become a master comic artist, you are going to have to keep drafting work.”

On the subject of first drafts:

A quote from Anne Lamott’s Bird by Bird: Some Instructions on Writing and Life

That blank page is the worst sometimes! It stares at you and says “I dare you to try doing something great. Betcha won’t though! HAHAHA!” (yet another reason I used to put X’s in my work). My first Life Drawing teacher once spoke about this and told us if the blank page was that intimidating, don’t draw on it. He told us to get a newspaper or a book, and draw on top of that. He told us he would ride the subway sometimes doing caricatures of people on the top of newspapers, to get in the habit of drawing regularly as opposed to drawing with a goal in mind.

“For me and most of the other writers I know, writing is not rapturous. In fact, the only way I can get anything written at all is to write really, really s—– first drafts.

The first draft is the child’s draft, where you let it all pour out and then let it romp all over the place, knowing that no one is going to see it and that you can shape it later. You just let this childlike part of you channel whatever voices and visions come through and onto the page. If one of the characters wants to say, ‘Well, so what, Mr. Poopy Pants?,’ you let her. No one is going to see it. If the kid wants to get into really sentimental, weepy, emotional territory, you let him. Just get it all down on paper because there may be something great in those six crazy pages that you would never have gotten to by more rational, grown-up means. There may be something in the very last line of the very last paragraph on page six that you just love, that is so beautiful or wild that you now know what you’re supposed to be writing about, more or less, or in what direction you might go — but there was no way to get to this without first getting through the first five and a half pages.”

An excerpt from Anne Lamott’s Bird by Bird: Some Instructions on Writing and Life

So I tell my students, and myself, that you should only plan on getting 10-20% out of your first draft that you can actually use. If there is more than that — great! You have less work to do on your second draft. The point of that first draft is writing 100% of your thoughts to get to the 20% that really work. The rest is part of your learning experience. This is the time for you to play, make mistakes, and write your comic the way it is in your head.

makingcomics.com

Well said! I never even throw my old drawings away because I love seeing my growth as an artist. (and I’m sentimental haha)

The more you don’t think too long about blank pages, be it in writing or drawing, and just start (even if you just put a square or a circle on the page) the more you’ll notice you will become less precious about the things you draw.

And it helps not only througout time too. I notice that I don’t endlessly fidget with drawings anymore. I loosely sketch, if it looks crappy I shrug and try again on another area of the paper or a new sheet. Then, sometimes after multiple tries you even see your understanding of a subject grow over the course of an hour.

What also helps heaps is to do studies beforehand. As Chris Oatley (chrisoatley.com, a great podcat about this is “improve your art before you start) said: why does every artist on the planet (dancers, actors, singers) rehearse except for us illustrators?

We expect stuff to be perfect on the first try, I do as well but that’s ridiculous even. Yes, if you’re a seasoned dancer it’ll probably look better on the first try than someone who only has a few years of experience, but even then. Thy can make something good, great.

So in order to rehearse your drawings, gather extensive reference, do studies of everything that will appear in your paintings, do tons and tons of thumbnails (seriously, some illustrators will not start their drawing untill they have at least 100 thumbnails to truly find some composition they didn’t do before, if you keep them small and simple that doesn’t even need to take that long) do colour tryouts and then, when you start your drawing or comic page it’ll come out much better and you’ll have learned tons of new things in the process.

*gets off soapbox*

I only recently discovered all this and I have been drawing for 25 years. So I totally recognize this Patrick. I wrote about this experience in a blogpost here:

Great response! Thanks for weighing in Henrike – and if you find that Chris Oatley podcast be sure to share it. We would love it for our archives. Thanks!

Here’s a link to that podcast (I couldn’t resist searching for it… Sounded like a good listen)… http://chrisoatley.com/ep55improveartb4start/

Thanks for the great article!

What Jay said. 🙂

I recommend any artcast and blogpost by chris Oatley. Tons of great stuff on his site and in his academy. 🙂

On thumbnails. I used to not make thumbnails or sketches of what i was going to draw before i did it. But at some point I looked at all of the eraser marks on my “final copy” and realized I was already making drafts – just in a very inconvenient place. So now, for every comic page I draw, there are a stack of scrap paper sketches on the side. It is a great way to use old paperwork from your day job, cut it up into quarters and leave it in a pile at your desk. You will never feel bad about starting a dozen crappy sketches if it was on paper used for inventory reports or staff meeting agendas…

This is my new favorite article from MC.com (including the comments). Absolutely Brilliant. How many drafts did it take Patrick? 😉

All is said : “You have little control over how an audience experiences your work”

It should be used as a motivational poster or a “Making Comics Mantra” 🙂

I just finished to write a chapter, and I’m not even sure if I’ve done 10 or more versions of it. But from what I know, taking the time to rework and rework on a story is the best way to get amazing characters, surprising scenes, polished dialogues, etc, etc…

I call this method the “Draft and Reboot”, because I always end up integrating an idea (or a chapter) to another : I do this until I’m satisfied, until I have the feeling everything is connected.

Of course this method can be more costly for beginners, because I don’t think it works if you don’t already several stories in your pocket, or a story made up of many different pieces.

But as always, you get out of it what you put in it… It’s just a matter of time.