One of the things I enjoy most about writing is how varied the form can become, both technically as well as thematically, while still telling the same story. I spoke with Brent Weeks (The Night Angel Trilogy, The Lightbringer Series) about crossing that line and adapting an already well established novel into a graphic novel with his book, The Way of Shadows (Weeks, Brandon, Macdonald). As a newcomer into the comic-creationverse (that’s definitely a thing now), Brent had quite a bit to say about the experience of collaboration and what went into the process of adaptation.

Kevin Cullen: In your interview with Orbit, they brought up the collaborative nature of graphic novels – from working alongside artists to editors to even script adapters. Was there any facet of working with this larger group of collaborators that you felt was challenging and/or rewarding? Was there anything from that process that you took away that you might apply to your own solo work?

Brent Weeks: The first time you do anything, it’s a little challenging to work out what you do and what your part on the team is going to be. On top of that, in artistic fields like graphic novel writing, every project is different, so I would sometimes ask what the expectation of my part was to be — and the answer would consistently be, “It depends what you want.” Having not written graphic novels with anyone else, I had no idea what the normal baseline was, so that led to some inefficiency in the process.

Brent Weeks: The first time you do anything, it’s a little challenging to work out what you do and what your part on the team is going to be. On top of that, in artistic fields like graphic novel writing, every project is different, so I would sometimes ask what the expectation of my part was to be — and the answer would consistently be, “It depends what you want.” Having not written graphic novels with anyone else, I had no idea what the normal baseline was, so that led to some inefficiency in the process.

To offset that, of course, is that you have creative minds working together, all trying to make something great, and bringing different strengths to the table. So three or four people with different gifts working hard together can do more than I could have ever done by myself.

[Tweet “I think graphic novels need more simplicity @BrentWeeks”]

Any collaborative work is going to be very different than the freedom of writing a novel. But I certainly learned some things that I would use if I were to write more graphic novels in the future, or stand-alone graphic novels that aren’t adaptations of my novels. I think graphic novels need more simplicity and can pick up their richness in nuance and in the finer points of the art, rather than layers of plot twists.

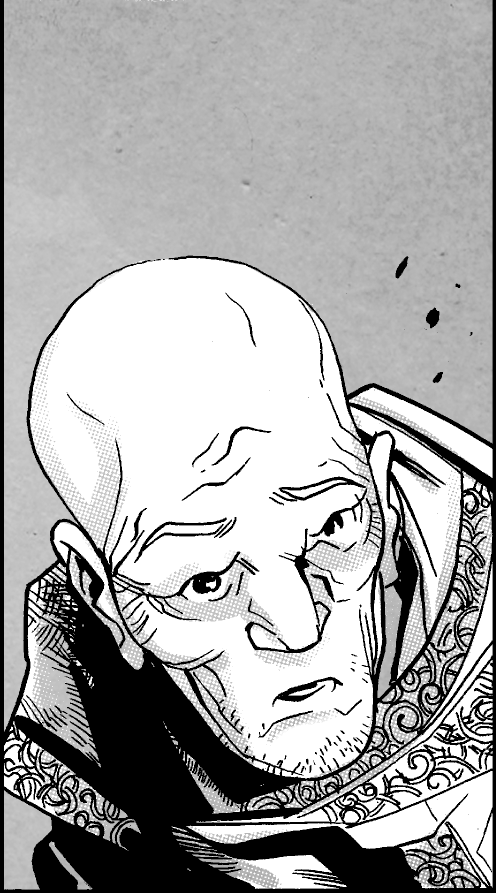

KC: The characters you create are very nuanced, each one with his or her own very identifiable voice. When moving into the realm of graphic narrative, writers are challenged with creating not only individual voices, but very visual presences as well. This is something your graphic novel does extremely well as the physicality of each character is readily apparent and harmonious with their individual voices. As a writer shifting from prose to scripting a graphic novel, were there any significant changes that you had to make to the characters or any lengthy discussions you had to have with Andy in order to ensure that your characters had the visual presence you wanted for them? Or was it more of a “let the artist do what he does best and see what happens” kind of thing?

BW: We started with pulling all the quotes that described the characters physically, and sending those to Andy and seeing what he came up with. His art then gave us a baseline. In most of the cases, it was amazing, or the deviations from what I had in my own mind still aligned with the text. In a couple of cases we further clarified and mentioned things like, “Hey, Logan has to be as tall as his dad, even though at this point in the Trilogy, he doesn’t have the sheer physical presence.” It can be an interesting balance to strike because in real life, two guys could be the same size, but carry themselves very differently. And one will strike you as being really big, while the other doesn’t simply because of their athleticism or their grace or whatever. In a graphic novel, you have to change the physical representation a little bit to convey the feeling instead. Honestly, I love the work Andy did with all the character designs.

[Tweet “you have to change the physical representation a little bit to convey the feeling instead. @BrentWeeks”]

KC: Shifting to setting – different writers have different rituals to ease themselves into the scenes they’re putting to paper. Some of them like to visit the locations they’re writing about or peruse Google Images for ideas about locations, while others like to draw upon their imaginations or memories from long ago while they sit comfortably in a coffee shop. Do you have a routine that you like to employ that helps you submerge yourself in the setting? Do you think it’s important to have a routine when it comes to world building (or writing in general)? And do your routines differ when writing prose vs. scripting?

BW: I don’t think I have a routine that I can discern — so maybe I should try this! In my style of writing, it’s more a matter of trying to submerge myself into a particular character. Azoth moving around the streets of a slum feels totally different than I would. When he sees trash and vomit on the street, those barely stick out to him, because they’re part of his world, they’re just something to get past and not get on your feet, where if you put me in the same situation, I’d be disgusted and highly aware of whether I was in danger or if I was going to get a disease or something. So to me the setting comes through the characters’ feelings about their environment.

[Tweet “So to me the setting comes through the characters’ feelings about their environment. @BrentWeeks”]

KC: I’ve never heard of exploring one’s setting like that, but the more I think about it, the more sense it makes – exploring the scenery through the eyes of someone who’s actually in the scenery. How about when it comes to designing the maps that your books are known for? Do you do much research into different types of topography and how they might affect your story when choosing what kinds of lands to include?

BW: Yeah, there’s a certain amount of research involved. I remember looking at a fantasy novel when I was a kid (I’ll leave it nameless here, but it was a big one), and one of the coastlines was essentially square. I mean, almost a 90 degree angle. That’s really nice if you want to fit a lot of detail onto a page, when the designer is laying out the map to fit in a book which also (surprise, surprise) has 90 degree angles at the bottom left corner! Later books in that series, and later editions, cleaned up that map and made it look a little less artificial, but you want your land to look natural, and at the same time interesting, so I did consult various earth maps while I was construction my own, because I believe that topography has a huge influence on history. If you live on the Great Plains, the only natural borders you have are rivers, and rivers don’t make good defenses. Thus, there’s almost no good way to stop raids if you live in the American West or on the steppes of Mongolia. On the other hand, if you live in the Swiss Alps, you can live in peace as long as you control a few very tight mountain passes. But at the same time, if you live in those mountain passes, it’s going to be very difficult for you to have an empire, because mountains aren’t very good at growing food, so you’re going to end up sending out your second through sixth child out away from the farm to make their way in the wider world. This is why Swiss mercenaries were a thing. So I tried to incorporate some of those ideas into my work.

KC: Let’s get technical for a second. With the milieu of scripting programs available (many of which are free, many also which are not), writers might be hard pressed to choose between any single one as loyalties and bad reviews abound for just about any software out there. Which writing program (be it Word, Scrivener, Celtix, etc.) did you use and why? What was it that drew you to using that program? And do you utilize something similar in your novel writing or do you pull a George RR Martin and hunker down with a DOS computer?

BW: I should be clear that my scripting here was following on the heels of Ivan Brandon, who first made the adaptation into a script. So the majority of my contributions were closer to editing than to straight-up scripting. So I was able to make do with making most of my corrections in Word/Pages or even email. If I’d been starting from the blank page, I might have bought scripting software. I’m afraid that what I ended up sending to my editor, JuYoun Lee, was fairly ugly and took some translation sometimes. For novel writing, I used Word for my first four novels, and my last two I’ve used Scrivener. I find Scrivener to be amazing for composition, but once you get to the editing phase of the business with tracking changes and seeing markups and accepting or rejecting changes and so forth, you end up having to use Word anyway. (Or one of the Word equivalent programs.)

[Tweet ” I used Word for my first four novels, and my last two I’ve used Scrivener. @BrentWeeks”]

KC: Same here. For initial writing, I do it all in Scrivener, then transfer it over to Google Docs so I can get a few editors working on it at the same time all in one place. I’m glad you mentioned Ivan Brandon, as I was interested in his role in the process. Were the two of you in much contact during his adaptation of the novel? Or did you wait for him to finish the adaptation, allowing you to make the necessary edits with JuYoun Lee after he was done?

BW: Most of my work on the script came after Ivan Brandon was done, although certainly JuYoun was talking with him as we were working through the chapters as well. I think it’s different every time and with every project. He did a great job of simplifying the story to its basic elements and presenting the key ingredients.

KC: One thing that your stories are known for are the abundance of twists that throw readers through emotional gamuts. Is there a storyboarding technique or process that you adhere to while plotting such intricacies to help you navigate the twists and turns of the narrative when your books are collectively thousands of pages? To add onto that, the level of seemingly insignificant details that later on become incredibly important are everywhere! How do you manage to keep those small details in your story when the graphic novels need to be condensed to only a couple hundred pages?

BW: I wish I could tell you, because if I could figure out exactly how I did it, I could probably streamline the process for myself and do it better! One of my tricks is using my short attention span as a strength instead of a weakness. If I see that I’m doing something in my plot that I’ve seen numerous times before, it makes me bored. So I end up asking myself, “Can I do something here that’s more interesting, that’s still consistent with what I’ve told already, and that also will keep me on the path to go where I want to go?” Then it’s just a matter of the hard work of going back through and making sure that what you remembered fits. Many, many drafts.

For the graphic novel, this was one of the greatest problems I faced. You simply don’t have the textual space to insert everything. So I spent a lot of time making cuts and then trying to figure out what those cuts were going to screw up in the rest of the book, and later in the Trilogy. Whether I did that well or not is up to readers to decide.

That’s a really interesting observation about topography influencing history.

To illustrate novels is not so common skill developed by comics makers…it should be a hard effort to do with a team of drawers, editors, writters…this article is very helpful…